My first column looked into the history of technological development in Japan and its special characteristics.

Japan was closed to the outside until the Meiji Era (1868), but still learned, adapted and perfected techniques. Craftsmanship was widespread and well regarded, silken kimonos and swords being prime examples. “Monozukuri“—making things—was deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

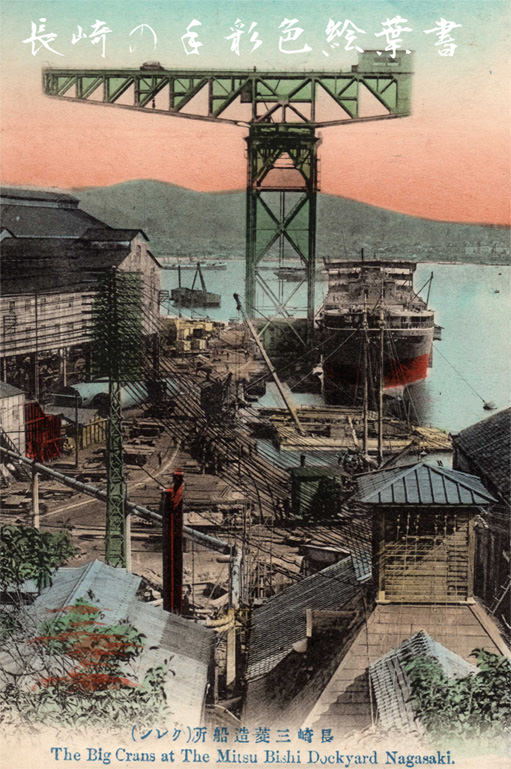

The country had strongly industrialized until World War II. It was dominated by big industrial groups like the Zaibatsu, which were linked to families like Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo and Yasuda, but also other companies transformed into such groups.

For the adaptation of technology as well as the creation of own new knowledge, Japanese companies had sometimes even several research laboratories. This trend increased sharply during wartime. Hitachi for example opened its new central research facility in the 1940’s.

Shift toward civil products after World War II

This technological base and also the structure became very valuable when Japan shifted its industrial production from military toward civil products after the war.

First of course, demilitarization became important. The Zaibatsu, which were dominating the industry, were dissolved of their family ties. Outside shareholders were allowed and the inside structure became less more flexible.

Soon after, however, Japan’s reindustrialization became important for the U.S. for geopolitical reasons. The existing industrial structures were needed and the industrial groups mainly remained, albeit less centralized. This new strategy was accompanied by a favorable technology licensing policy for Japan.

Changes occurred also on the side of the government. It became clear that science and technology was vital for the future of Japan.

So in 1949 the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) was newly constituted from some existing bodies. It became the dominant architect of Japans industrial recovery.

Its first white paper on technology was published the same year. Titled “The State of Our Country’s Industrial Technology,” it stated the need for Japan to develop technologies that are directly applicable in industrial production.

Public research was streamlined. Under the MITI, the Agency for Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) was set up to consolidate several government laboratories. However, their outcome was not sufficient to supplement the industry with adequate technology necessary for the transition to civil products.

So foreign technologies were continually imported. During the 1950s, the number of scientists in industrial laboratories doubled, applying and combining these technologies with own innovations to make them commercially successful.

Research Associations and Big Projects

The 60s saw the rise of a new trend. MITI started the Industrial Technology Research Associations with the goal to develop original and precompetitive technologies.

The Associations were to handle so-called “Big Projects.” These were projects too costly to be financed by single companies, but expected to generate important new knowledge. A crucial characteristic was that after the end of each project, the participating firms could share and develop the results into own products, thus creating new competitive power for themselves.

The AIST got the task to set up these projects and coordinate the research done by the companies, to a big part in laboratories set up at the AIST.

One of the very successful Big Projects was the VLSI (Very Large Scale Integration) project from 1976-1980 to develop the next generation of microchips. The VLSI Cooperative Research Association included NEC, Fujitsu, Hitachi, Toshiba and Mitsubishi Electric. Some further equipment companies also profited from the technologies developed and it considerably advanced the Japanese electronics makers up to a leading position worldwide.

Photo: Hitachi Central Research Laboratory, (c) Hitachi Ltd.

Such Big Projects, the licensing policy and the efforts of the industry went hand in hand and often supported the industrial rise of Japan. This continued for three decades until the bubble economy with sky-high property prices burst at the end of the 1980s.

Before that, Japan had already shocked the world at the end of the 70s with fully automated automobile production lines—where robots did the assembly, which was still done with manual labor in the U.S. and Europe. But not alone with regard to cars; in the 1980s Japan produced the majority of the world consumer electronics products.

The specifics of the Japanese science and technology system described in this column developed in the early days and the wartime. They were not significantly changed after World War II and proved good for Japans miraculous economic rise. They still remain today. First: The Japanese economy remains characterized by big industrial groups that do considerably more research by themselves than in other countries.

Secondly: public research is still strongly shaped and influenced by the ministries— and therefore also depending on their strategy.

Finally, public R&D projects are often still organized as Research Associations, involving all relevant companies, with good exchange of information and developing precompetitive technologies.

In the next column we will have a closer look at developments in and after the bubble economy.