Almost two million jobs have been created since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office in 2012. This is good news for employees, but companies are having difficulties finding the people they need. “With 1.5 jobs per seeker, Japan is now facing the most extreme labor market since 1974,” said Hays Japan Managing Director Marc Burrage while presenting the recruitment specialist’s latest Global Skills Index 2017 report in Tokyo.

The tight labor market comes as the country’s population is shrinking while its economy experiences a sustained phase of growth. Elder people are already staying in the workforce longer, but according to Burrage, this can only be a temporary fill. He predicts the situation is “set to worsen.”

The tight labor market comes as the country’s population is shrinking while its economy experiences a sustained phase of growth. Elder people are already staying in the workforce longer, but according to Burrage, this can only be a temporary fill. He predicts the situation is “set to worsen.”

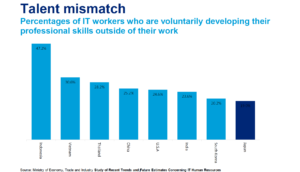

To complicate matters, Japan faces a serious talent mismatch. Its labor market ranks second worst among the 33 countries surveyed, which means that there is a significant gap between the skills available in the workforce and those needed today.

So Why Do Existing Skills Not Match Required Skills?

According to Burrage, workers’ skills are not maintaining pace with technological progress.

For one, Japanese society puts great score on academic credentials, so people tend to stop studying after having achieved the desired degree. Moreover, universities are seen as places to become educated and cultivated; they focus less on the acquisition of practical professional skills.

Workers’ skills are not maintaining pace with technological progress.

Then there are structural factors. According to a survey by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), workers in Japan are reluctant to upskill themselves: Jobs are safe due to lifetime employment, and seniority-based pay means that salaries do not properly reflect skills anyhow.

Annual salary guides regularly confirm this finding: Many Japanese companies still have seniority-based payment structures, and salaries for high-skilled workers are significantly lower than in other countries.

Which Skills Are Most Sought After in Japan’s Labor Market?

The talent mismatch is especially significant in rapidly growing sectors such as Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence. This includes data scientists, autonomous driving engineers, AI engineers and IoT experts. It is a global phenomenon: Hays data indicates that wages in rapidly growing fields in the U.S. or Germany are already 50 percent higher than in Japan.

The talent mismatch is especially significant in rapidly growing sectors such as Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence. This includes data scientists, autonomous driving engineers, AI engineers and IoT experts. It is a global phenomenon: Hays data indicates that wages in rapidly growing fields in the U.S. or Germany are already 50 percent higher than in Japan.

A METI survey says that Japan has been short of 170,000 IT staff in 2016, and predicts that this gap could quadruple by 2030. With the domestic talent pool shrinking, the country urgently needs to address this challenge. As former CEO of Nissan Motors Carlos Ghosn pointedly said, the “Japanese automobile industry cannot afford to lose the global war for talent.”

Current Moves by the Japanese Government

Japan’s government is aware of the challenge and is already taking various measures. This includes a shift to more practical education, including compulsory programming lessons at primary schools from 2020 onwards. However, education takes time.

So, with a view toward quicker results, the country is relaxing visa requirements for highly-skilled foreign professionals, and is trying to attract immigrants with advanced IT skills. As part of this initiative, Japan invites students from the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) to spend internships at Japanese firms through a program called Project Indian Institutes of Technology (PIITs).

Yet there are difficulties: Not as many people seem to stay as hoped. For one, Japan is not overly attractive to foreign workers: at rank 77 in the World Economic Forum’s 2016-17 Global Competitiveness Report, Japan is significantly outranked by India at 22. Moreover, due to various reasons ranging from socioeconomic conditions and cultural mindset in many companies, Burrage points out that the country labor market is currently not prepared to offer what foreign talent really needs: A career.

3 Ways to Make Japan’s Workforce Fit for the Future

Based on the findings of its Global Skills Index, Hays recommends tackling the challenge by pursuing a mix of short-term, mid-term and long-term initiatives at the same time.

1. Long-term: Build What Japan Needs

To ensure Japan’s future competitiveness, it has to build education and training systems that produce the skills in line with the needs of the future rather than the past. Individuals will need to upskill themselves to a larger degree than they do today – and such self-development needs to be encouraged. This will require an effort from both the government and business, explains Burrage.

Introduction of new technology may present an opportunity, as it may be partially offset population decline. Yet it may also replace people who want to work but do not have the necessary skill set. So it will be extremely important to strategically educate and upskill people to make sure that they will not be left behind while the Fourth Industrial Revolution progresses in strides.

2. Mid-term: Adapt – Retrain and Redeploy

In the mid-term, seniority-based compensation needs to be reformed. The current system overprotects regular employees and favors older people. Young people with the urgently required skill sets outlined above find their growth potential limited and, looking to the future, will increasingly move abroad.

Deregulation instead will favor young people and women. Higher labor market liquidity and skill-based compensation typically leads to higher productivity and thus higher company performance. At the same time, it will also work to lessen the severe gap in pay and recognition between regular and non-regular staff – with the latter largely comprised of women and already making up 40 percent of Japan’s labor force.

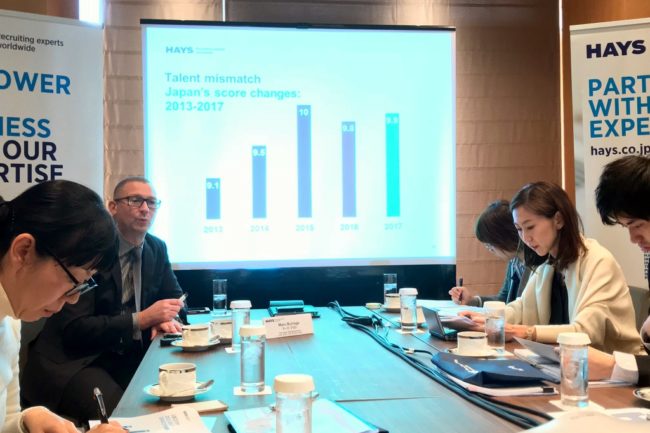

Hays Japan Managing Director Marc Burrage presents the Global Skills Index 2017

Hays Japan Managing Director Marc Burrage presents the Global Skills Index 2017

According to Burrage, this structural reform will be very difficult but must be a priority. “It’s a challenge and an opportunity at the same time,” he said.

3. Short-term: Buy What Japan Needs

The acceptance of highly-skilled foreign professionals needs to be hastened to bridge an urgent current gap and to gain time for developing the required skills.

The government is already following policy of easing requirements for foreign workers since 2013. They are now estimated to number around one million, up 20 percent year-on-year and up the fourth year in a row. A new Green Card and the ability to fast-track permanent residency is expected still within this year. Yet so far only around 600,000 of all foreign workers in Japan can be considered highly-skilled.

This number is far too insufficient, said Burrage. And while Japan is attracting tourists at a rapid pace, for high-skilled workers the country is often in the news for the wrong reasons, such as death from overwork or lack of diversity. To attract foreign talent quickly, he points out that especially the issues of work-life balance and acceptance of a diverse workforce need to be addressed.

The Biggest Challenge of All

There are many challenges, but there are also many solutions that can be implemented. Yet those solutions are not easy. Importing foreign labor, adapting pay and promotion systems and changing education will require structural and cultural change. “And this,” concludes Burrage, “may be the biggest challenge of all.”

No comments yet.